Fuses are designed to stop excess current flow that can overheat circuits, damage equipment, or even cause a fire. To account for normal electrical spikes and surges, vehicle designers typically specify fuses with amp ratings of double the current flow a circuit will see under normal conditions. In automotive applications, there are push in/pull out flat fuses which resemble teeth, and there are cylindrically-shaped fuses which snap in place at both ends. Both serve the same purpose, and they function in similar ways. In this article, we’ll examine how to remove, inspect, and test these fuses using electrical test equipment.

Tools and Equipment Needed:

-Flashlight (traditional or LED)

-Small flathead screwdriver

-Fuse pulling tool piece or needle-nose pliers

-Multimeter/Voltmeter or test light

-Replacement fuses (if replacing is necessary)

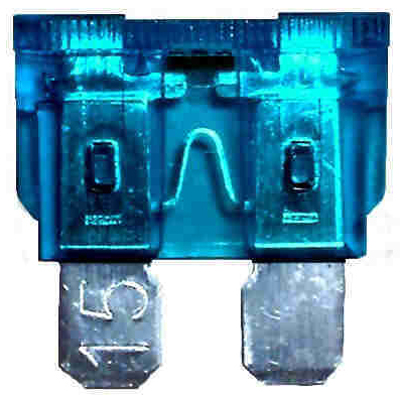

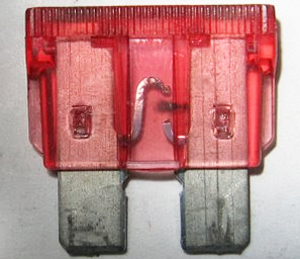

Shown here is a flat, “blade fuse” fuse most commonly found in automotive applications. A conductive (horseshoe-shaped) metal strip runs through an outer plastic housing, and will appear unbroken to the eye if the fuse is good.

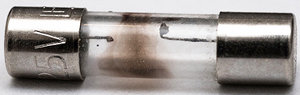

Shown in this picture is a cylindrically-shaped “glass fuse” found in some automotive applications. Also known as “Buss fuses” after the manufacturer Buss, a conductive metal strip runs down the center and will appear unbroken to the eye if the fuse is good.

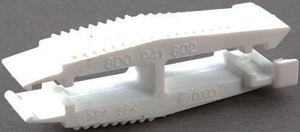

Older European cars often use this type of “ceramic fuse” built with an outer conductive surface made of copper or other metals that surrounds a ceramic center support piece. The narrow part of the copper piece will break in the middle when the fuse blows.

Most automotive fuses are grouped together behind a removable plastic panel located under the dash, or on the edge of the dash as shown in this photo.

If an electrical item on your vehicle stops working, the first thing to do is check the fuse for the circuit that the non-working part runs on. When a fuse has more electricity flowing through it than it can safely handle, a conductive metal strip running through the center is designed to literally break apart to ensure all current is interrupted.

VISIBLY INSPECTING A FUSE

Whatever their design, fuses will be clearly labeled with their ampere ratings. When replacing a fuse, insert one with the exact same rating as the one being removed. Chip style fuses shown here pull out using a special tool designed to grab the end piece.

Using the owner’s manual, locate where the fuses are. If you don’t have an owner’s manual, a quick internet search or call to the manufacturer should produce the information. On many vehicles, fuses may be lined up behind a panel under the dash or on a side of the dash obscured by the driver’s door when closed. On other makes and models, fuses may be contained in a box under the hood. Fuse panels and fuse boxes have a cover piece that may require a small flathead screwdriver to remove. On the back of the cover piece, you’ll find a diagram which shows you the position of each fuse so you can locate the one you need to check.

A typical fuse-pulling tool of plastic construction which grabs onto the colored cap at the top of a fuse. Most automakers supply these inside the fuse panel.

Physically remove the fuse using a small, specially shaped fuse puller tool. The tool serves to clamp around the numbered outer edge of the fuse that you can see. Some vehicles include this tool stored within the fuse box. Once you’ve got a grip on the fuse, wiggle it out by pulling gently toward you in the same fashion you’d pull a tooth. If you don’t have a fuse-pulling tool, a pair of needle-nose pliers will provide the grip and maneuverability you need. Use caution to ensure you do not “short” the metal part of the pliers against a live circuit.

Once the fuse is out, inspect the metal wire piece inside of it. A visibly broken metal strip indicates the fuse has blown and needs to be replaced. Install a new fuse with the same amperage rating – usually the vehicle manufacturer provides extras in the fuse panel. Under no circumstances should a replacement with a lower or greater amp rating be used.

This photo shows a blade style fuse that has blown and no longer functions. Notice the conductive metal strip is broken in the middle.

This photo shows a glass fuse that has blown and no longer functions because of the broken conductive metal strip that runs down the middle.

While bad fuses are usually easy to spot by looking at them, don’t assume a fuse is good or functioning perfectly if the metal strip appears intact. A fracture in the strip could be obscured out of sight behind the opaque plastic end cap. Electrically testing the fuse with a multimeter tool is recommended in order to be sure.

ELECTRICALLY TESTING A FUSE THAT HAS BEEN REMOVED

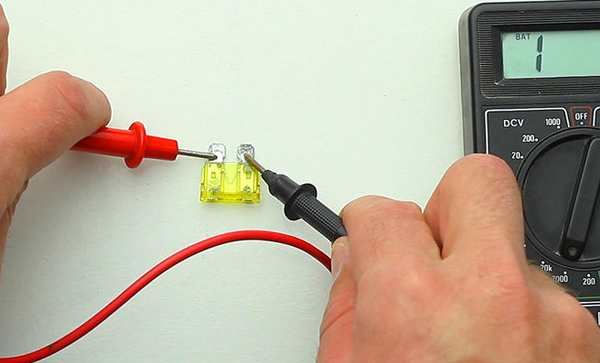

Testing a fuse can be done with either a multimeter (shown above) or a simple test light. If using a multimeter, set the dial on Ohms. Touch the red lead on one metal end of the fuse and touch the black lead point on the other metal end of the fuse. If the fuse is fine, the multimeter will show a resistance reading. A blown fuse will result in no reading. If using a test light, touch the lead to each side of the fuse. A blown fuse will light on one side but not the other.

Testing a fuse can be done with either a multimeter (shown above) or a simple test light. If using a multimeter, set the dial on Ohms. Touch the red lead on one metal end of the fuse and touch the black lead point on the other metal end of the fuse. If the fuse is fine, the multimeter will show a resistance reading. A blown fuse will result in no reading. If using a test light, touch the lead to each side of the fuse. A blown fuse will light on one side but not the other.

ELECTRICALLY TESTING A FUSE WITHOUT REMOVING IT

If you don’t want to risk breaking electrical continuity to whatever component the fuse handles by pulling it out, a fuse can be checked while still in place using a test light (shown in the picture on the right). With the ignition switch in the on position, attach the black ground clamp to any unpainted metal object nearby. Using a multimeter to test a live fuse in place is not recommended.

If you don’t want to risk breaking electrical continuity to whatever component the fuse handles by pulling it out, a fuse can be checked while still in place using a test light (shown in the picture on the right). With the ignition switch in the on position, attach the black ground clamp to any unpainted metal object nearby. Using a multimeter to test a live fuse in place is not recommended.

On the end cap of a blade fuse, you’ll see two exposed areas of metal designed for testing. Touch the lead of the test light to the first metal square, then to the other. If only one side generates a current reading, the fuse is bad. Readings on both sides of the fuse indicate it’s working properly and a problem exists somewhere downstream of the fuse. If neither side yields a reading, there is no current flowing into the fuse to begin with – indicating an electrical problem upstream of where the fuse is.

REPLACING A FUSE

If you’ve determined a replacement fuse is necessary, gently press a new one of the same voltage into the designated slot and check to see if your dead part is now operative. Fuses blow from time to time, and there’s no need for concern if the problem does not reoccur. Should the new fuse blow relatively quickly, more electrical diagnosis will be needed to test and track down the source of the improperly high current.