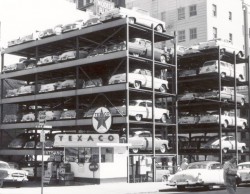

Can you tell an Oldsmobile from a Buick in this photo? Here, a street scene in Brandon, Vermont is captured during the late 1940s.

Walking through a parking lot with my mother started the debate. “All cars look alike these days”, she said. “Back in the 1940s, you could distinguish the different makes easily. I could tell the type of every car the adults had in my neighborhood growing up.”

Being a car fan since I could walk in the early 1970s, I knew I could make a similar claim for cars produced in my own lifetime. I told my mother no chance, she was wrong. How could ‘40s cars be more recognizable when, to me, they all seem to resemble upside-down bathtubs? If anything, it was the cars I remembered growing up with that looked the most different from each other. But it occurred to me I could not recall many times my mother was able to distinguish one car make from another with any great success. Perhaps if she could recognize ‘40s cars as well as an enthusiast could, then maybe that decade really did produce the cars that were easiest to tell apart. Or was it simply a result of the mind’s natural ability to absorb more details in one’s most formative young years?

I recalled a 1940s-era picture of a row of cars on a city street in a Life Magazine coffee table book I had once seen. A black-and-white picture that had faded to shades of brown, it was the type of picture that pulled the viewer in and gave him or her the illusion of what life would’ve been like walking down this given street at this given moment. At third, fourth, and even fifth glance all I could be sure of was every one of the cars in the picture parked diagonally along the road was black, some had two doors and some had four, they varied in size but not in shape, and that I could not distinguish the make of any of them. While 1940s Cadillacs, Packards, Lincolns, and Chrysler Town & Countrys are more recognizable, none could be found in this picture. This street view showed a place and time where there was a distinct absence of such cars for the wealthy.

I recalled a 1940s-era picture of a row of cars on a city street in a Life Magazine coffee table book I had once seen. A black-and-white picture that had faded to shades of brown, it was the type of picture that pulled the viewer in and gave him or her the illusion of what life would’ve been like walking down this given street at this given moment. At third, fourth, and even fifth glance all I could be sure of was every one of the cars in the picture parked diagonally along the road was black, some had two doors and some had four, they varied in size but not in shape, and that I could not distinguish the make of any of them. While 1940s Cadillacs, Packards, Lincolns, and Chrysler Town & Countrys are more recognizable, none could be found in this picture. This street view showed a place and time where there was a distinct absence of such cars for the wealthy.

It got me thinking while styles come and go, every decade (even my mother’s favorite one) has its copycat designs. Do automobiles really look any more or less different now than the ones from any other decade? Is there any one ten-year period of automotive design where the most commonly sold cars were more recognizable from each other walking down a typical street? And considering I was born in 1968 and never experienced 1940s and ’50s cars up close enough to have learned them by osmosis, would I be able to figure out answer to that question easily?

It made sense to start with cars of my mother’s decade (the 1940s) because prior to that, reference information becomes scarce. In this quest to find the decade that produced the most recognizable cars as a whole, I approached this semi-scientifically – digging out both reference books on cars with lots of pictures, and tracing paper. I would level the playing field by tracing the shapes of popular models I was to compare, without shading or drawing in windows or wheel well openings. This would be equivalent to seeing a car in dim twilight, and only the truly distinctive cars could stand out on this kind of test – no matter what decade they were from. At times I found myself needing to go back and draw in more details before a Chevy could be told from a Ford, A Buick from an AMC. To adjust for waning car recognition skills prior to my birth year, I enlisted two uncles who have always been car guys as judges to assist.

Studying the books, one first sees 1940 cars as tall and ponderous with fenders that looked like pontoons, hoods with a bulbous bulge down the center, trunks that were more vertical than horizontal and, of course, running boards that several men could stand on. With the exception of a cargo bed behind the front seat, even pickup trucks from this era were not much different between the front bumper and the front door.

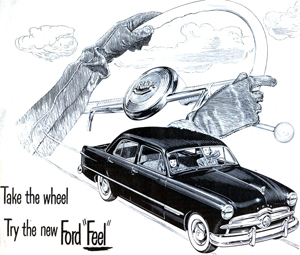

It seemed the clearest automotive styling break of the 1940s occurred when the redesigned 1949 Ford became the first American car to eschew most of the trademark design cues of that decade. Aesthetically, it was five or six years ahead of Chevrolet and Dodge.

It seemed the clearest styling break of the whole decade was when the redesigned 1949 Ford became the first American car to eschew most of the trademark design cues of ’40s cars. Aesthetically, it was probably five or six years ahead of Chevrolet and Dodge – a lifetime of difference considering the period. After doing a lot of tracing, my uncles agreed 1940s cars that stood out the clearest were the ones with long, elegant proportions – a prime example being Packards before they were redesigned after the war. Cadillacs stand out as a shape also, especially once tail fins sprouted on 1948 models. Otherwise, 90 percent of other vehicles sold in the U.S. during that time could not be told apart on tracing paper. Sports cars weren’t around yet, imports weren’t around yet, and the front half of pickup trucks weren’t even discernible from cars. The scientific ruling was low differentiation for the 1940s category.

In 1950, most American cars carried over the look of their 1940s predecessors with pontoon style fenders, high pointy hoods, and bloated styling. This 1950 Buick Special is shown as an example.

Early 1950s American cars carried over the look of their ’40s predecessors while becoming lower and sanded down. A chunkier, integrated look that became increasingly sporty and aerodynamic with each passing year was taking over. One favored design that seemed to embody all that was futuristic at the beginning of the decade was the 1950 Mercury – a customized example of which made an appearance in the 1986 Sylvester Stallone film “Cobra”. From 1950 through 1954, hood designs became gradually more flattened out. Running boards which were still quite pronounced in 1950 were reduced more and more until they were mere trim pieces. Rear fenders became less and less pontoon-like each year. Almost every American manufacturer followed this same formula through 1954.

The basic Chevrolet and Dodge models of 1955 finally adapted flat hoods and integrated fenders – a much cleaner and fresher look which brought them up to the more modern appearance started with the 1949 Ford. (1955 Chevrolet shown)

The basic Chevy and Dodge of 1955 finally both came on the scene with flat hoods and fenders – a much cleaner and fresher look which finally brought them up to the more modern appearance that began with the 1949 Ford. From this point forward Ford, Dodge, and Chevrolet obviously knew what each other was doing because they delivered the same basic look at the same time. 1956 models remained mostly unchanged, and for 1957 Ford and Chevrolet made minor yet similar changes, adding fins almost to the same proportion.

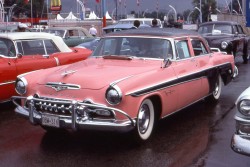

Chrysler caught its bigger competitors napping when 1957 Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, and Chrysler mainstream models increased vehicle length and width while moving from 2 to 4 headlights and adding fins – something the others wouldn’t do to their basic cars until 1958.

Chrysler caught its bigger competitors napping when 1957 Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, and Chrysler mainstream models increased vehicle length and width while moving from 2 to 4 headlights and adding fins – something the others wouldn’t do to their basic cars until 1958. Once the lower-wider-longer look became the norm, styling between Ford, GM, and Chrysler looked more unique than at any other point during that decade. Kudos also belongs to the 1956-57 Lincoln Continental Mark II which was a very low-production, expensive coupe of great length. Unlike other Lincolns of the 1950s, it was ahead of its time and almost impossible to mistake for anything else.

Because sports cars, fins, and imports such as Volkswagen came on the scene during the 1950s, we agreed that decade beat the 1940s thus far based on sheer variety of automotive shapes and styling.

Cadillacs from the 1950s are recognizable on tracing paper because of tail fins which were consistently the largest in the industry since the wreath-and-crest division pioneered them in 1948. Studebaker models became recognizable on tracing paper about 1949 and continued more so as the ‘50s progressed. Most of their models were very distinctive, with the exception of “Parkview” and “Broadmoor” models which imitated prior year Chevrolet and Oldsmobile styling almost identically. Buicks and Packards are handsome designs distinguishable from other big cars during this era as well. Looking closely at those two brands from 1948 through 1954, it seems as if Packard stylists learned exactly what Buick designers were up to, and promptly mimicked them. After that Packard designs followed a page out of the Chrysler Imperial styling book until Packard’s demise in 1958. Greater variety was added to the landscape by popular sports cars such as the 1953 Corvette and the 1955 Ford T-Bird – both with distinct, recognizable profiles. And variety was also added by Volkswagen who, after entering the U.S. in 1950, made a significant market presence for the 1956 model year by selling a total of 50,000 Beetles, Karmann Ghias, and vans – none of which could be mistaken for anything else.

On the strength of all these factors, we agreed the 1950s beat the 1940s thus far based on sheer variety.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Select any of the pictures below to expand them to full size. Click on the small arrows underneath the picture to scroll backward or forward.

- Can you tell an Oldsmobile from a Buick in this photo? Here, a street scene in Brandon, Vermont is captured during the late 1940s.

- According to my mother, “All cars look alike these days. Back in the 1940s, you could distinguish the different makes easily. I could tell the type of every car the adults had in my neighborhood growing up.” We began a scientific analysis of automotive designs from each decade to see if that statement was correct.

- While automotive styles come and go, every decade (even my mother’s favorite one) has its copycat designs. Do automobiles really look any more or less different now than the ones from any other time frame? Is there any one ten-year period of automotive design where the most commonly sold cars were more recognizable from each other walking down a typical street?

- Packard styling before World War II is much more recognizable. After the war through 1954, it seems as if Packard stylists learned exactly what Buick designers were up to and promptly mimicked them. After that Packard designs followed a page out of the Chrysler Imperial styling book until Packard’s demise in 1958. So Packard added a point to the 1940s category, but not the 1950s.

- While highly-recognizable European sports cars and roadsters were available in the United States during the 1940s, it was only in small numbers. Their popularity grew during the 1950s.

- Often, those who were not around during the 1940s tend to see cars from that decade as tall and ponderous with fenders that looked like pontoons, hoods with a bulbous bulge down the center, and trunks that were more vertical than horizontal. With the exception of a cargo bed behind the front seat, even pickup trucks from this era were not much different between the front bumper and the front door.

- Enlisting the help of two uncles who were car guys, we agreed a more distinctive 1940s design were Chrysler Town and Country models. While other cars offered wood styling, none were as large and distinctively shaped as these Chryslers through 1940. Thus, these cars scored a point for the 1940s category.

- Cadillacs stand out as a shape also, especially once tail fins sprouted on 1948 models. Otherwise, 90 percent of other vehicles sold in the U.S. during that time could not be told apart on tracing paper.

- One of the clearest styling breaks of the 1940s decade was when the redesigned 1949 Ford became the first American car to eschew most of the trademark design cues of ’40s cars. Aesthetically, it was probably five or six years ahead of Chevrolet and Dodge.

- The 1949-54 Jaguar XK models (1949 model shown) were uniquely styled. Like most European sports cars, their simple presence was not felt in the United States until the 1950s.

- In 1950, most American cars carried over the look of their 1940s predecessors with pontoon style fenders, high pointy hoods, and bloated styling. This 1950 Buick Special is shown as an example.

- The 1951-54 Kaiser Henry J model was an inexpensive, compact car with big-car styling. Because of its size, we felt it was uniquely recognizable – adding a distinction point to the 1950s.

- Greater variety was added to the 1950s landscape by popular sports cars such as the 1953 Corvette. This first-generation Corvette ran in basically the same form through 1962.

- Also contributing to 1950s American automotive variety was another never-seen-before 1955-57 Ford Thunderbird. Like the Corvette, its distinct shape is instantly recognizable on tracing paper.

- The basic Chevrolet and Dodge models of 1955 finally adapted flat hoods and integrated fenders – a much cleaner and fresher look which brought them up to the more modern appearance started with the 1949 Ford. (1955 Chevrolet shown)

- 1955 Chrysler division styling also followed in the footsteps of the 1949 Ford. (1955 DeSoto Fireflite shown).

- The Triumph TR3 of 1957-62 offered lower-priced European sports car motoring. Because cars like this were completely lacking in the 1940s, we gave a point to the 1950s decade for these type of vehicles.

- The introduction of the Nash Metropolitan microcar during the later half of the 1950s added another uniquely recognizable profile that hadn’t been seen before in the U.S. We added a point for them because of their popularity.

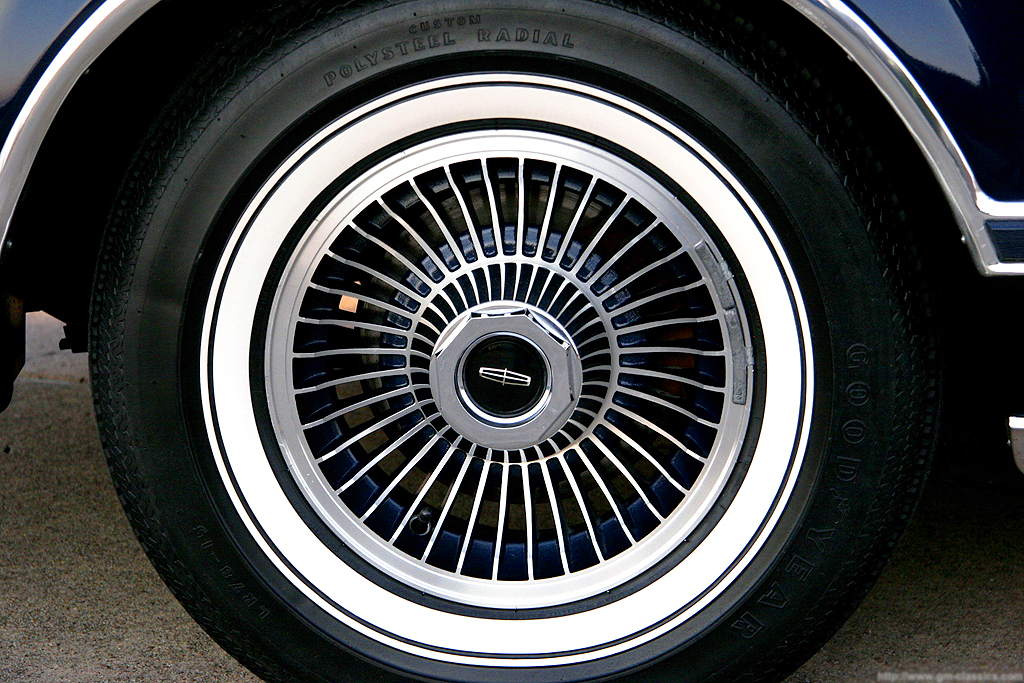

- The low-production 1956-57 Lincoln Continental Mark II provided another shape that was easily recognizable on tracing paper. We didn’t give it a full point because of its low production numbers and high price tag.

- Chrysler caught its bigger competitors napping when 1957 Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, and Chrysler mainstream models increased vehicle length and width while moving from 2 to 4 headlights and adding fins – something the others wouldn’t do to their basic cars until 1958.

- Variety was also added by Volkswagen who, after entering the U.S. in 1950, made a significant market presence for the 1956 model year by selling a total of 50,000 Beetles, Karmann Ghias, and vans – none of which could be mistaken for anything else.

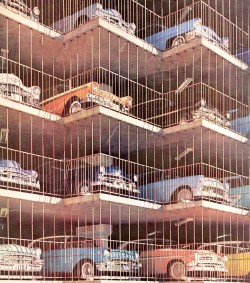

- This street scene shows a number of 1950s automobiles.

- This street scene photographed before Christmas in 1958 gives a glimpse at the typical automotive landscape in the United States.

- Because sports cars, fins, and imports such as Volkswagen came on the scene during the 1950s, we agreed that decade beat the 1940s thus far based on sheer variety of automotive shapes and styling.

I would have thought the same thing a few years ago. Once you start learning about the circumstances impacting the design of these cars, such as material availabilty and engineering advancement, the form follows a natural course. It wasn’t until the 1950’s through the early 1960’s that form diverted from function to the extent that all of the big car companies had to reel back their styling ambitions. Examples include the stratospheric 1959 Cadillac fins, the pod-lamped 1961 Imperial, and the Elwood Engel Continentals Mark III, IV, and V, truly worthy of being named for a large land mass. Each 40’s car has different curves to the fenders, very different details in brigh twork (admittedly Buick followed Chevrolet or vice versa in several areas), and as a historical note, running boards fell out of fashion as early as 1940 when the 1941 models arrived late in the year. As a scientist, you need to be very careful not to let your hypothesis affect your analysis of the data.