Paddle shifters mounted behind left and right side steering wheel spokes originated in the 1990s on Formula 1 race cars, and first appeared on street versions of Porsche 911s and Ferraris. A quick pull on either allows a corresponding gear change up or down. (Photo credit: H. Harris)

(By contributor John Bleimaier)

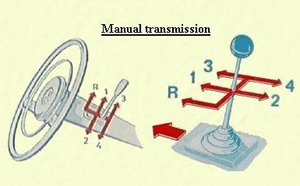

The advent of paddle shifters in today’s cars should cause us to consider once again where the gear shift lever should ideally be placed. Paddle shifters located on either side of the steering wheel and affixed to the steering column allow for a manual override of automatic transmission function.

Derived from racing competition applications, paddle placement was decided upon because the gear changes could be effected without the driver having to move his hands from the wheel.

Current production car paddle shifter application is exclusively in the context of automatic transmissions, many of which are race car style clutchless manual gearboxes internally. I’ve always felt any transmission without a clutch pedal is inherently inferior as it removes the possibility of feathering engagement and eliminates an element of control, not to mention driving pleasure.

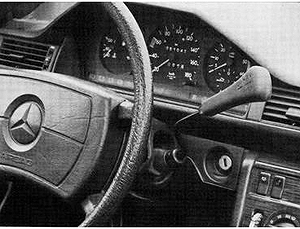

A diagram showing manual column shifting operation of a ’65 Mercedes 190 Diesel 4-speed. (Photo credit: P. Schneider)

However, the placement of the gear selector in the immediate proximity of the

steering wheel is laudable. My 1965 Mercedes has the manual gear change on the steering column (four-on-the-tree, if you will), and on the basis of personal experience I can assure you that once a person gets used to this setup, it becomes the most natural-feeling place for the gear shifter.

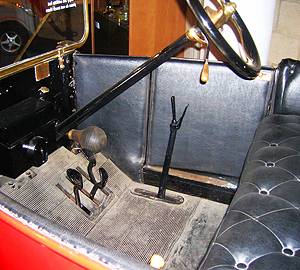

Before gear shift linkages were created, the earliest automobiles had floor-mounted gear shift levers which were bolted directly into the transmission itself. Ford Model T shown. (Photo credit: W. Anderson)

Because shifting is now in the same plane as steering, the distance a driver’s hands must travel is minimized. With well designed linkages, as found in Mercedes-Benzes of the ‘50s and ’60s, the feel is crisp and the engagement is direct. Very satisfying. Indeed, during that period many of the finest sporting Alfa Romeos, Lancias and Saabs had column-mounted manual transmissions. They were wonderful, enthusiast vehicles. Saab and the Mercedes competition cars which won the prestigious Monte Carlo rallies during that era were all equipped with four-on-the-tree.

The idea of having the gear selector on the

Once transmission shift linkages were developed in the 1920s, designers had freedom to place gear shift levers in more ergonomic positions. Here, a right-hand-drive 1938 Delahaye roadster features a 3-speed manual controlled by a small shifter at the end of a steering-column mounted stalk. (Photo credit: W. Smith)

floor dates from the time when the lever more or less directly actuated the shifting of the cogs in the transmission with virtually no extraneous linkages. This was a simple and inexpensive arrangement from a design and manufacturing perspective. However, once a series of linkages is introduced, placement of gear shift levers can be the lever can be dictated by ergonomics alone. Thus the development of the column-mounted manual shifter.

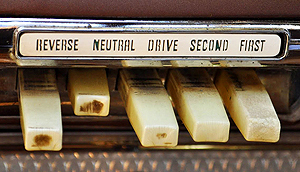

During the 1950s, automakers (particularly Chrysler) experimented with dash-mounted pushbutton controls for automatic transmissions. This kind of alternate trend is poised to make a comeback. (Photo credit: Just a car guy)

Subsequently the concept of “four-on-the-floor” became a marketing rather than an engineering principle. Madison Avenue decided that the gearshift should be located between the driver’s and passenger’s seats. Then followed the greatest boondoggle of all time, the placement of an automatic transmission selector on the floor. There is no conceivable engineering justification for moving from “P” to “D” with a lever sprouting from the floor.

Mercedes-Benz last sold cars equipped with column-mounted gearshift levers in the U.S. in 1973. As this interior picture of a 1989 300E shows, such models were still produced for other world markets. (Photo credit: C. Collins)

Besides the ergonomic and sporting arguments for placement of the gear selector on the steering column, this makes for more flexible use of automotive

interior space. In a pinch I have been able to seat six passengers in my Finback

because there is nothing projecting from my drive shaft tunnel. I also have more

room for my right knee, even when I am alone in the vehicle.

Center consoles that take up valuable passenger space and leg room exist because marketers have told us we need them, not because they serve any vital function. Shown, a 2010 Volkswagen Touareg. (Photo credit: Sean Connor)

During the 1970s and ‘80s the abomination known as the center console arrived on the scene. The center console, ostensibly justified by the presence of the gear selector on the floor, narrowed the driver and the passenger’s footwells. Narrow footwells mean leg cramps on long journeys. In most cars the center console encapsulates a substantial amount of dead space between the instrument faces and the firewall. I would pay extra if the reduction or elimination of the center console was made an option.

As I write this, temperature and humidity are soaring toward the century mark. Heat tends to focus our judgmental complaints and foster a spirit of griping and

As transmission shift linkages once did, the use of electronic controls allows more versatility in placing gearshift controls. Shown is a dash-mounted rotary knob control to be equipped on all 2013 Dodge Ram trucks. (Photo credit: G. Vasilash)

testiness. I recognize this. However, I respectfully submit that automotive designers should not confine themselves to the cool aviaries of the air conditioned studio. They should undertake field research in the sweaty, real world. Particularly, folks who brought us the center console should be sent on assignment to Death Valley.

-John

(Contributor John Bleimaier is an attorney at law, active Mercedes-Benz club officer, and automotive journalist for The Star magazine.)

1969 Volkswagen Karmann Ghia wheelPhoto: Genna Rae

1969 Volkswagen Karmann Ghia wheelPhoto: Genna Rae 1969 Volkswagen Karmann GhiaPhoto: Genna Rae

1969 Volkswagen Karmann GhiaPhoto: Genna Rae 50s Calnevar aftermarket hubcaps shPhoto credit: T. Gorski

50s Calnevar aftermarket hubcaps shPhoto credit: T. Gorski Chrysler LeBaron Town & Country wheel cover

Chrysler LeBaron Town & Country wheel cover Cadillac Eldorado painted wheel cover 1976-78Photo: Nate Smith

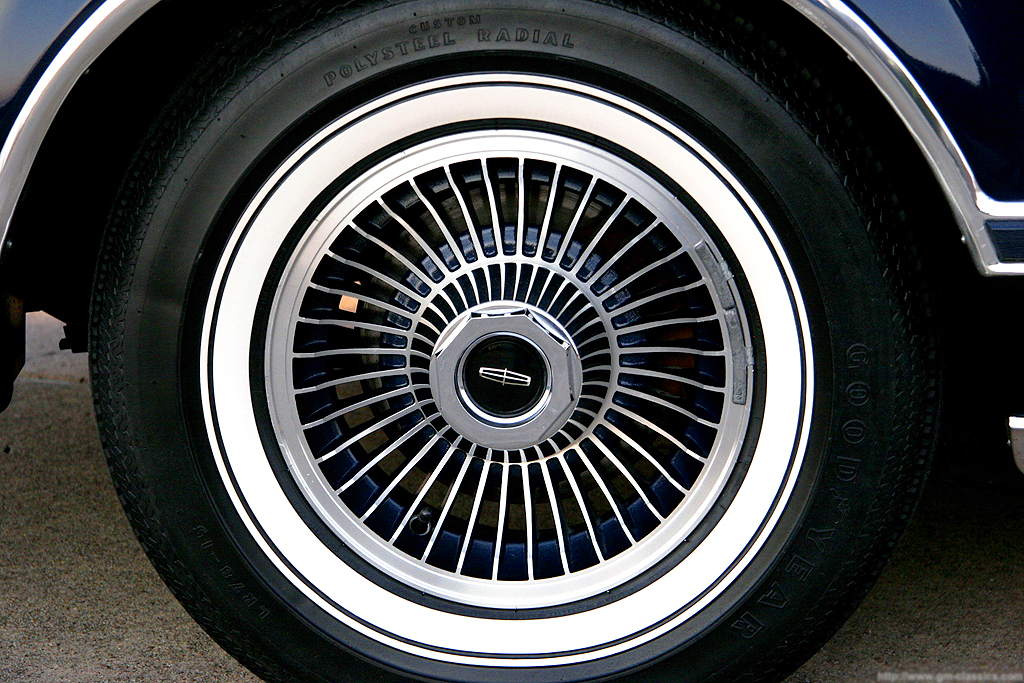

Cadillac Eldorado painted wheel cover 1976-78Photo: Nate Smith 1974 - 1976 Lincoln Continental wheel coverPhoto credit: H. Carver

1974 - 1976 Lincoln Continental wheel coverPhoto credit: H. Carver 1969 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme rallye wheelPhoto: C. DeMarco

1969 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme rallye wheelPhoto: C. DeMarco Chrysler 1980s painted wheel coverPhoto: O. Stein

Chrysler 1980s painted wheel coverPhoto: O. Stein 13-inch General Motors color matched wheel 1975-80Photo: Valley Ride Styles

13-inch General Motors color matched wheel 1975-80Photo: Valley Ride Styles Audi TT RS wheelPhoto: Sean Connor

Audi TT RS wheelPhoto: Sean Connor 1994 - 1995 Mercedes E320 Cabriolet wheel

1994 - 1995 Mercedes E320 Cabriolet wheel 2012 Volkswagen Beetle 2.5 standard wheel

2012 Volkswagen Beetle 2.5 standard wheel 16-inch black steel Land Rover off-road wheelsPhoto credit: J. Getty

16-inch black steel Land Rover off-road wheelsPhoto credit: J. Getty 18-inch aluminum wheel on 2003 - 2004 Land Rover Discovery HSE

18-inch aluminum wheel on 2003 - 2004 Land Rover Discovery HSE 18 inch "Hurricane" aluminum wheel standard on 2002-2004 Discovery SE

18 inch "Hurricane" aluminum wheel standard on 2002-2004 Discovery SE 1957 - 1958 Pontiac wire wheel cover(Photo credit: R. Ulrich)

1957 - 1958 Pontiac wire wheel cover(Photo credit: R. Ulrich) 1972 Mercedes 280SE 4.5 equipped with repro 15-inch alloy wheels(Photo credit: Sean Connor)

1972 Mercedes 280SE 4.5 equipped with repro 15-inch alloy wheels(Photo credit: Sean Connor) 560SL 15-inch aluminum wheel

560SL 15-inch aluminum wheel 1981 Porsche 924 Carrera GT aluminum wheel

1981 Porsche 924 Carrera GT aluminum wheel 1978 Lincoln Mark V DJ blue wheel b(Photo credit: M. Garrett)

1978 Lincoln Mark V DJ blue wheel b(Photo credit: M. Garrett) 1979 Lincoln Mark V Collectors Series navy blue painted wheel(Photo credit: M. Garrett)

1979 Lincoln Mark V Collectors Series navy blue painted wheel(Photo credit: M. Garrett) 1969 Dodge Charger RT Hemi wheel with center hub cap

1969 Dodge Charger RT Hemi wheel with center hub cap 1953 Oldsmobile wire-wheel

1953 Oldsmobile wire-wheel 2014 Jaguar XK RS GT wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show(Photo credit: Sean Connor)

2014 Jaguar XK RS GT wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show(Photo credit: Sean Connor) 2014 Mercedes CLA45 AMG wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show(Photo credit: Sean Connor)

2014 Mercedes CLA45 AMG wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show(Photo credit: Sean Connor) 2013 Subaru WRX concept wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show

2013 Subaru WRX concept wheel at the 2013 New York Auto Show 1952 Volkswagen wheelPhoto credit: L. Jacobs

1952 Volkswagen wheelPhoto credit: L. Jacobs 1975 Pontiac Grand Ville rallye wheelPhoto credit: Sean Connor

1975 Pontiac Grand Ville rallye wheelPhoto credit: Sean Connor 1991 Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham wire wheel cover

1991 Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham wire wheel cover Dodge Charger all-black police car wheel a

Dodge Charger all-black police car wheel a Dodge Charger all-black police car wheel b

Dodge Charger all-black police car wheel b 1963 Mercedes 230SL wheel at the 2013 June Jamboree in Montvale, NJPhoto: Sean Connor

1963 Mercedes 230SL wheel at the 2013 June Jamboree in Montvale, NJPhoto: Sean Connor 1964 Mercedes 230SL wheel at the 2013 Mercedes-Benz June JamboreePhoto: Kristi Burns

1964 Mercedes 230SL wheel at the 2013 Mercedes-Benz June JamboreePhoto: Kristi Burns

Commentary – Popularity of today’s paddle shifters reminds us the best place for gear shifting really is on the steering column.

Paddle shifters mounted behind left and right side steering wheel spokes originated in the 1990s on Formula 1 race cars, and first appeared on street versions of Porsche 911s and Ferraris. A quick pull on either allows a corresponding gear change up or down. (Photo credit: H. Harris)

(By contributor John Bleimaier)

The advent of paddle shifters in today’s cars should cause us to consider once again where the gear shift lever should ideally be placed. Paddle shifters located on either side of the steering wheel and affixed to the steering column allow for a manual override of automatic transmission function.

Derived from racing competition applications, paddle placement was decided upon because the gear changes could be effected without the driver having to move his hands from the wheel.

Current production car paddle shifter application is exclusively in the context of automatic transmissions, many of which are race car style clutchless manual gearboxes internally. I’ve always felt any transmission without a clutch pedal is inherently inferior as it removes the possibility of feathering engagement and eliminates an element of control, not to mention driving pleasure.

A diagram showing manual column shifting operation of a ’65 Mercedes 190 Diesel 4-speed. (Photo credit: P. Schneider)

However, the placement of the gear selector in the immediate proximity of the

steering wheel is laudable. My 1965 Mercedes has the manual gear change on the steering column (four-on-the-tree, if you will), and on the basis of personal experience I can assure you that once a person gets used to this setup, it becomes the most natural-feeling place for the gear shifter.

Before gear shift linkages were created, the earliest automobiles had floor-mounted gear shift levers which were bolted directly into the transmission itself. Ford Model T shown. (Photo credit: W. Anderson)

Because shifting is now in the same plane as steering, the distance a driver’s hands must travel is minimized. With well designed linkages, as found in Mercedes-Benzes of the ‘50s and ’60s, the feel is crisp and the engagement is direct. Very satisfying. Indeed, during that period many of the finest sporting Alfa Romeos, Lancias and Saabs had column-mounted manual transmissions. They were wonderful, enthusiast vehicles. Saab and the Mercedes competition cars which won the prestigious Monte Carlo rallies during that era were all equipped with four-on-the-tree.

The idea of having the gear selector on the

Once transmission shift linkages were developed in the 1920s, designers had freedom to place gear shift levers in more ergonomic positions. Here, a right-hand-drive 1938 Delahaye roadster features a 3-speed manual controlled by a small shifter at the end of a steering-column mounted stalk. (Photo credit: W. Smith)

floor dates from the time when the lever more or less directly actuated the shifting of the cogs in the transmission with virtually no extraneous linkages. This was a simple and inexpensive arrangement from a design and manufacturing perspective. However, once a series of linkages is introduced, placement of gear shift levers can be the lever can be dictated by ergonomics alone. Thus the development of the column-mounted manual shifter.

During the 1950s, automakers (particularly Chrysler) experimented with dash-mounted pushbutton controls for automatic transmissions. This kind of alternate trend is poised to make a comeback. (Photo credit: Just a car guy)

Subsequently the concept of “four-on-the-floor” became a marketing rather than an engineering principle. Madison Avenue decided that the gearshift should be located between the driver’s and passenger’s seats. Then followed the greatest boondoggle of all time, the placement of an automatic transmission selector on the floor. There is no conceivable engineering justification for moving from “P” to “D” with a lever sprouting from the floor.

Mercedes-Benz last sold cars equipped with column-mounted gearshift levers in the U.S. in 1973. As this interior picture of a 1989 300E shows, such models were still produced for other world markets. (Photo credit: C. Collins)

Besides the ergonomic and sporting arguments for placement of the gear selector on the steering column, this makes for more flexible use of automotive

interior space. In a pinch I have been able to seat six passengers in my Finback

because there is nothing projecting from my drive shaft tunnel. I also have more

room for my right knee, even when I am alone in the vehicle.

Center consoles that take up valuable passenger space and leg room exist because marketers have told us we need them, not because they serve any vital function. Shown, a 2010 Volkswagen Touareg. (Photo credit: Sean Connor)

During the 1970s and ‘80s the abomination known as the center console arrived on the scene. The center console, ostensibly justified by the presence of the gear selector on the floor, narrowed the driver and the passenger’s footwells. Narrow footwells mean leg cramps on long journeys. In most cars the center console encapsulates a substantial amount of dead space between the instrument faces and the firewall. I would pay extra if the reduction or elimination of the center console was made an option.

As I write this, temperature and humidity are soaring toward the century mark. Heat tends to focus our judgmental complaints and foster a spirit of griping and

As transmission shift linkages once did, the use of electronic controls allows more versatility in placing gearshift controls. Shown is a dash-mounted rotary knob control to be equipped on all 2013 Dodge Ram trucks. (Photo credit: G. Vasilash)

testiness. I recognize this. However, I respectfully submit that automotive designers should not confine themselves to the cool aviaries of the air conditioned studio. They should undertake field research in the sweaty, real world. Particularly, folks who brought us the center console should be sent on assignment to Death Valley.

-John

(Contributor John Bleimaier is an attorney at law, active Mercedes-Benz club officer, and automotive journalist for The Star magazine.)