When you’re into cars, it’s hard not to end up caring and worrying about the ones you own. You end up dodging potholes, choosing remote parking spots, spending money on maintenance items, keeping everything clean, using a car cover, and parking in a garage whenever one is available. If you’re one of our customers, you likely enjoy improving your cars with performance parts and other accessories.

Enter the “beater” car that’s way past its prime. This term can be used to define pretty much any vehicle that still has enough steam to get its owner around, isn’t worth much, and has a generally grim projection for future longevity. A beater car usually doesn’t look pretty, and it can easily require more money than it’s worth to fix everything wrong. In other words, a beat- up car that you don’t care about.

For the typical car fanatic, this can be extremely liberating. For those that live in cold climates, beaters are great for driving on salty roads while a nicer vehicle stays safe at home. Potholes, cramped city streets, risky parking areas, hauling dirty debris – there’s no limit to a beater’s usefulness. Sure you may be rolling down the road with a check engine light, freezing with no heater, and holding a steering wheel that’s way off center while your suspension bottoms out over the slightest bumps – but you’re saving money traveling economy class, so it’s alright to sacrifice some comfort.

Of course, sooner or later any beater car will need repair for problems that can’t be ignored. This thought is always in the back of your mind as you wonder what your breaking point for the car will be when it comes to repair expenses. When will it make more sense to cut losses and sell or even scrap instead of fixing it?

In answering that question about when it’s time to cut the cord and get rid of a beater, I hoped to find some kind of mathematical formula that could be applied to any situation. Unfortunately, I came up empty. Naturally, it’s advisable to follow the rule that no single repair expense should exceed the present value of the vehicle. Nor should monthly repair expenses average more than the cost of leasing a the cheapest bare-bones economy car new with $0 down (we say cheapest possible new car because saving money is the point).

It’s hard to argue against making any single repair that costs a couple of hundred dollars unless these kind of repairs are occurring every single month. Keeping repair bill invoices or parts receipts for the do-it-yourselfer is essential, because it’s easy to forget actual amounts spent over time. Once a track record of past repairs can be taken into consideration, deciding how to proceed is much easier. We’ll note that it’s advisable not to count the cost of repairs or upgrades done right after a beater is first purchased, because practically all used cars require that something be made right in the beginning.

Another important factor to consider is the down time and outside expenses involved with repairs. If you’re using a shop, will towing your beater there cost you anything? If you’ll be doing your own repairs, how long will it take for parts to arrive? And how much time will you need to set aside to do the work? If the beater is your only vehicle, how much will it cost to get where you need to go during the down time? Uber and rental car charges can add up quickly.

How you plan to use a beater can be a factor. A car that’s used only for traveling to and from a train station parking lot might continue to serve in unrepaired “limp condition” longer than one that’s subjected to long commutes with stop-and-go traffic. Last, but not least, factor in any strains the inconvenience and embarrassment of a broken-down vehicle can put on relationships with family, employers, and others you’re close to.

And when you do decide to sell it, it’s best to take yourself out of the seller’s mindset for a moment. Give yourself an honest answer to the question, “What price would I pay me for this car?” if you were the one buying it in its present condition. The answer may be a disappointing one, but staying realistic will help you sell any vehicle quicker and with less hassle.

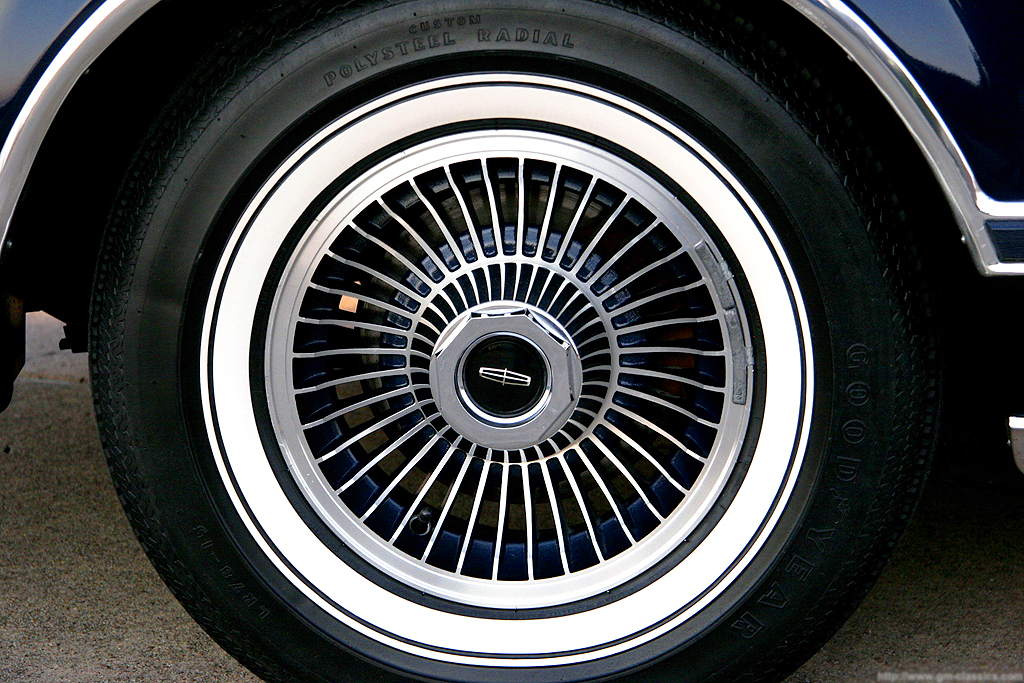

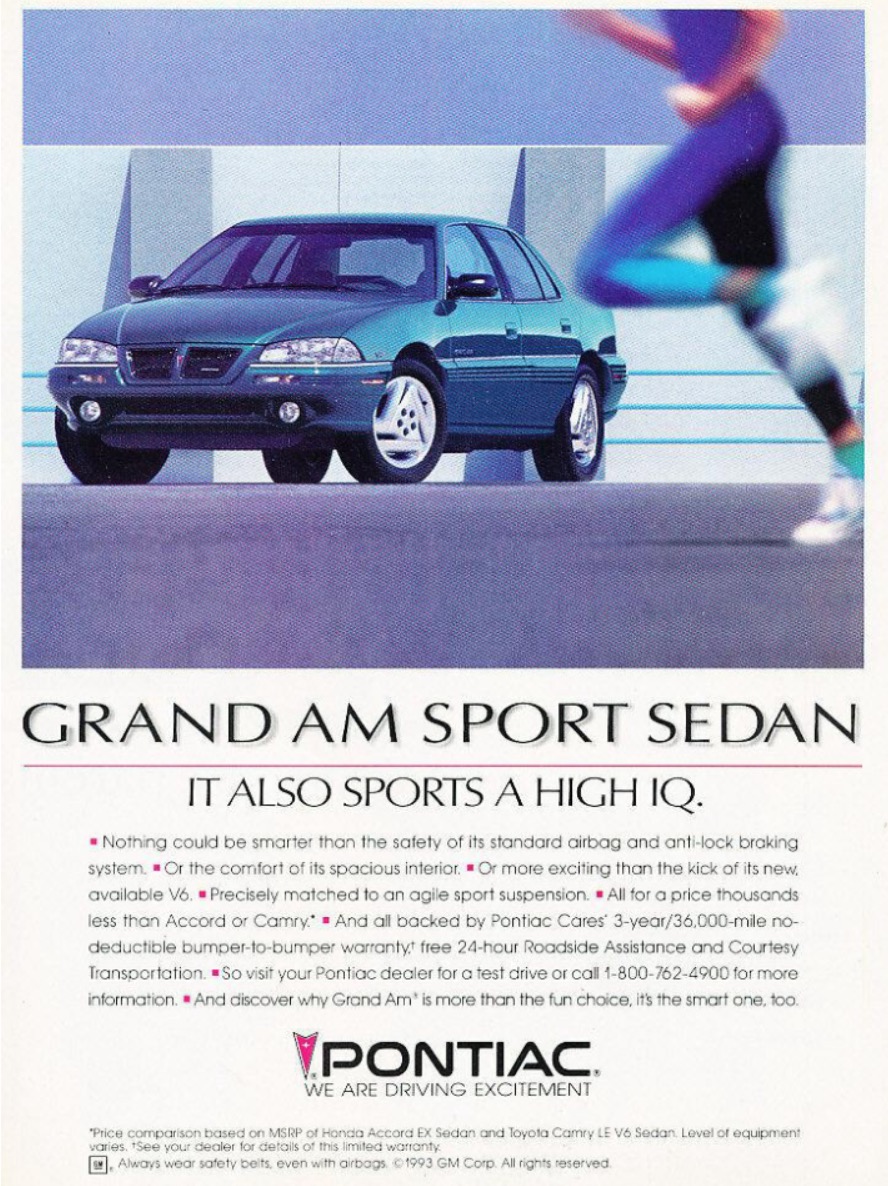

I’m going use a particular beater car I once owned as example of both good and bad cord- cutting decisions. In late 2004, I purchased a 1993 Pontiac Grand Am from a friend we’ll call Friend “A”, which I later sold to Friend “B” in 2005. Having been his first new car, A kept it looking and running decently past the 120,000 mile point. But when Friend A saw it become a financial drain and realized no dealership would offer him more than $200 as a trade-in, he opted to sell it to me for $300 instead. My pal simply wanted to get rid of it before something big blew up on him.

With front-wheel-drive, it performed well through winter snows, taking road salt in the face like a champ. With this many miles on a 1990s GM front-wheel-drive vehicle built to a low factory price point, I assumed all mechanical systems were ready to give up the ghost. If the car required much more than the price I paid for it, in the garbage it would go. The only repairs I ended up making were to replace the serpentine belt and tensioner myself up front, then later straightening the exhaust system and replacing an O2 sensor that bit the dust when a family member accidently drove the Grand Am up over a curb onto a street sign. Oh, and also, I replaced a blown tire with a used one I sourced from the back of the shop where I worked at the time. Other than that, my luck with the Grand Am was positive.

Shown here, an advertisement for the 1993 Pontiac Grand Am. This body style ran from model years 1992 through 1998.

When I replaced it with a 1993 Mercedes 190E equipped with snow tires that fall, friend B wanted the ’93 Grand Am because he, too, needed a beater car. After handing me $300, the car was his along with my strict advice not to spend much on it for anything. For some reason, he didn’t listen to me and got to liking the car – ignoring his inner voice and spending more than was practical on it. I’ll admit that with a 3.1-liter V6, the Grand Am had its charms and torque enough to spin the front tires.

After continuously driving with a low fuel level, the fuel pump died on B. He lived too far away for me to be of help to him, so he had it replaced at a shop. Then, the starter died. Then an electrical malfunction of the car’s built-in alarm system would intermittently prevent the engine from running. I believe the last thing he had fixed was the steering pump before the Grand Am was left to rot, immobile to this day in his back yard. In the end, Friend B easily got $300 worth of use out of it – but he also spent way more than the car was worth, and ended up with a vehicle that was never more than a bad day away from the junkyard.

What beaters have you owned?